My Story.

Just over four years ago, I was told that I had cancer. Since December 12th 2017 I have had several types of treatment, multiple surgeries and also periods of excellent health, cancer free. However now, after multiple recurrences and the spread of the cancer, I was told in summer of 2020 that my diagnosis was terminal. I have been living with this diagnosis for over a year, but following recent developments, the time now feels right to share the full story before I no longer get the chance to. This is not for want of sympathy, far from it. Instead, I would like everyone to have the full picture and to understand what my family and I have been through together because I am immensely proud of how we all have coped throughout, and some of my experiences might even help one or two people.

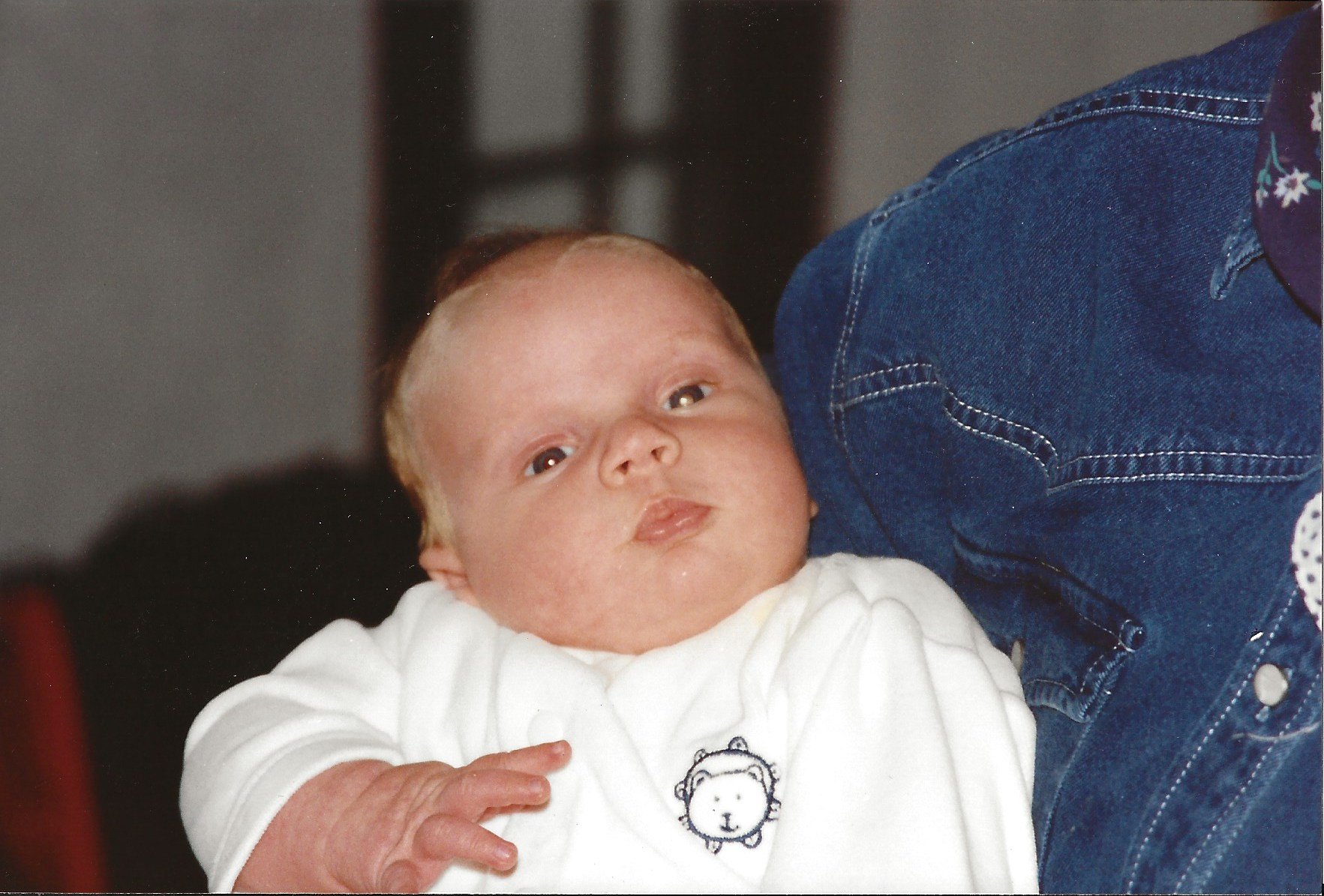

My diagnosis in 2017 was not my first encounter with cancer, and a lot of my friends will be learning that for the first time reading this. When I was 3 months old my parents were referred to a London hospital after suspecting something wasn’t quite right with my vision, and were told bluntly by an ophthalmologist; ‘Your son has cancer in both his eyes. We need to remove the left one straight away, and we are not sure if we will able to save the right one either’. You’ll be able to see the cancer in my eyes in the picture below - it is that white glow. For me as a small baby, it’s safe to say I had no idea what was going on. I was diagnosed with bilateral retinoblastoma (tumours in both eyes). My left eye was removed and replaced with a prosthesis. Some of my closest friends still don’t know that I have worn a prosthetic eye for my whole life - well now you do. More on that later…

My right eye was treated using lens sparing radiotherapy. At 3 months old I was given a general anaesthetic every day for 24 days in a row in order to have the radiotherapy. I was given the all clear in the following months. I was seriously lucky - my life had been saved by the removal of one eye, and I managed to retain my sight in the other one which needed treatment. Other children on the ward were not so lucky, either losing their sight altogether or even worse. Luckily treatment of this rare type of cancer found in 36 children per year in England has advanced, and 98% of children now survive but early diagnosis is really important.

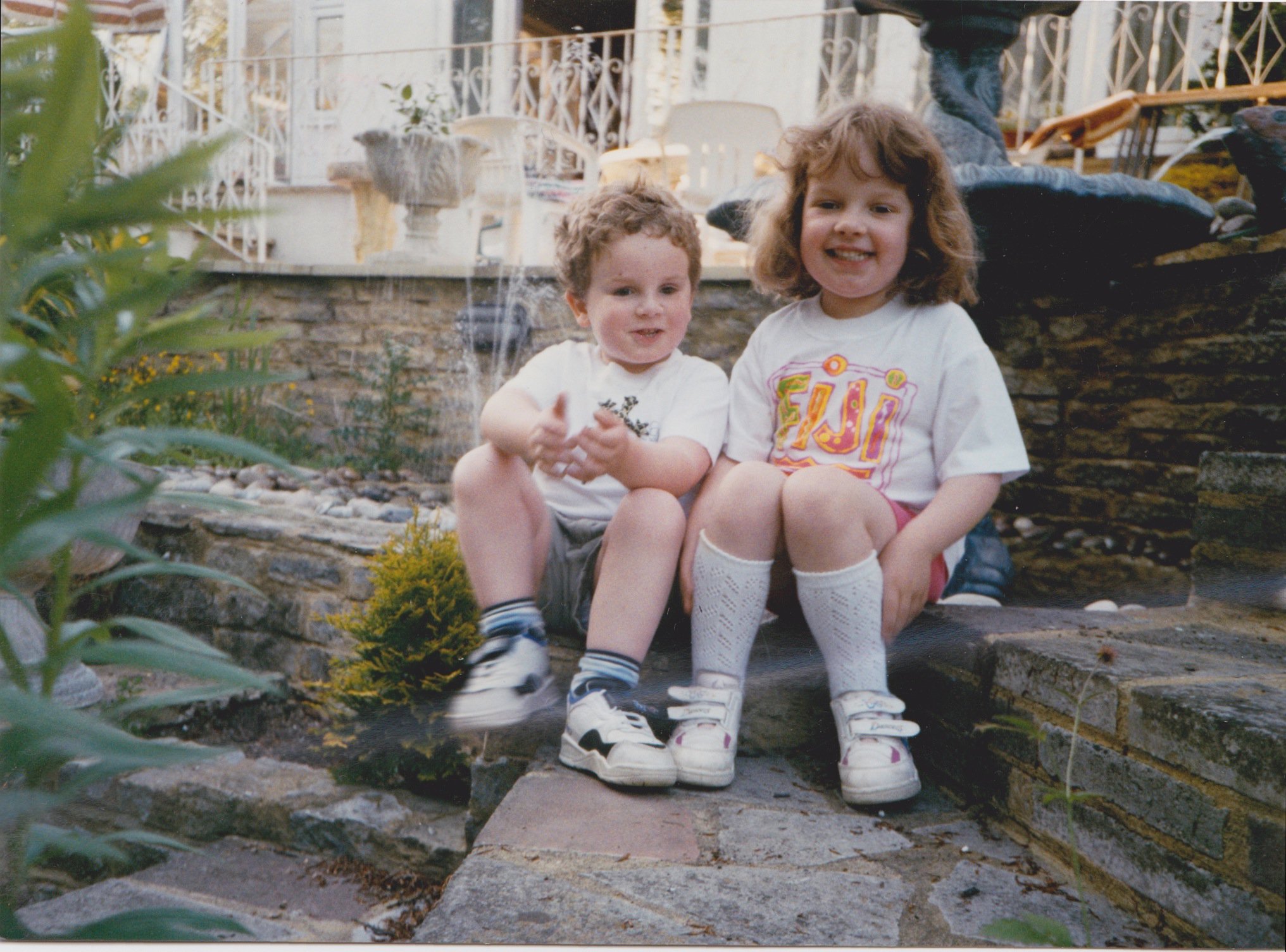

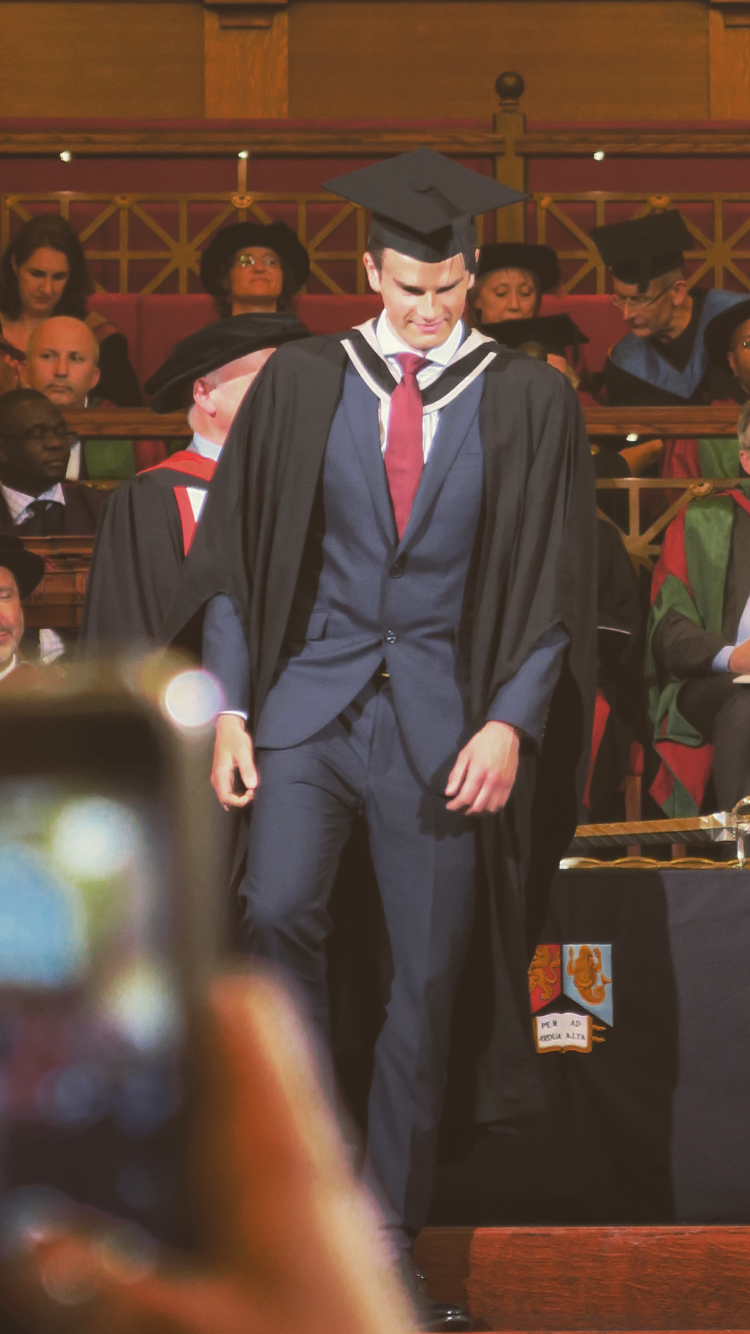

Fast forward a few years, numerous check ups, and the tumour in my right eye had returned at age three and then again at age five. Once again, at this age I was unaware - far too busy watching Fireman Sam and Pingu on the TV to have any idea what was going on. My parents went through it all again. Twice. Worrying about me and what would happen, but again, they knew I had no idea what was happening so hopefully that helped them in some small way. I have a few distant memories of trips to the hospital, and having to sit on my mums lap with my arms wrapped tightly around the back of her neck while they administered my anaesthetic into the back of my hand before my cryotherapy treatment. But that was it - no pain, no real worries. This time round the treatment had advanced - a few blasts of cryotherapy and I was given the all clear again. From that point on everything went well - I had an amazing childhood. I did relatively well at school, and got into a good university to study for my degree. I landed my dream job as a graduate, and was having a great time. Having retinoblastoma never held me back in achieving what I have wanted to do so far in my life.

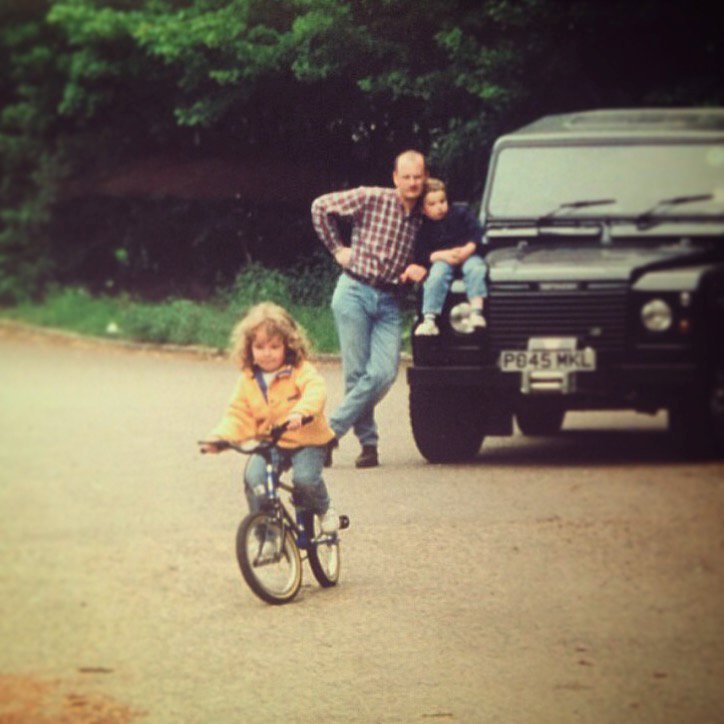

I grew up on a farm in the countryside, playing outside with our dog Meg, riding quad bikes and kicking a rugby ball or football around. I played rugby for my local club and for my school and loved it. I never wanted to go down to High Wycombe rugby club for that first training day one Sunday morning. I remember being about 10 years old and crying on the way there because I was so nervous about meeting new people and being self conscious. But my Dad knew it would be good for me in the long run, and took me there despite the protests. I am so grateful looking back that I had these moments of encouragement. As a family we were fortunate enough to go on some amazing holidays, the best of which for me involved learning to ski from the age of 6. Writing this is not to brag, instead I hope it shows that having retinoblastoma and vision in only one eye never stopped me giving things a go with a bit of encouragement. I am going to write an article on that for the Childhood Eye Cancer Trust which hopefully you will be able to read here soon. It also shows how fortunate I have been to have these incredible experiences, and for that I only have my parents to thank for encouraging, and always believing in me. I am so proud of them both, and I know that their lives and hard work have all been geared towards giving my sister and I the best lives and opportunities imaginable. I could not have asked for any more from them. When I look back writing this, looking through old photos, I can honestly say that in my 27 years of life to date I have truly lived.

Second cancers were always a risk as a result of the radiotherapy treatment I received as a small child, so each annual oncology checkup in London showing that nothing else had come back elsewhere was a real marker of progress for my family and I. However, in October 2017, aged 23, I began to get nosebleeds - nothing painful, I would just blow my nose and blood had begun to appear. This continued intermittently for a few weeks, sat at my desk at work with my nose spontaneously bleeding from time to time. After a visit to the doctor, a few appointments and referrals later, an MRI scan revealed that ‘an abnormality’ had shown up. I was told this over the phone while I was at work, and that I was going to need to return for a second scan for a more detailed look. I remember receiving that phone call in the office. It was a feeling of complete dread and helplessness. The next appointment would either culminate in total relief or complete dread. I had the follow-up scan and was told that I had a mass in my nose. In the words of the ENT surgeon who was investigating, ‘it might be polyp, it also might a tumour’. The following week I was booked in for surgery to take a biopsy of the mass that was in my left nasal cavity. Then another week of helpless waiting ensued - will it be nothing at all? Is it something more sinister? The second period of waiting for news was no easier than the first. On Tuesday 12th December we were called into the surgeons office; ‘the pathology results are back and it is showing to be a sarcoma’. This was a radiation-induced sarcoma that had arisen as a late effect of the lens sparing radiotherapy treatment that saved my vision and my life 23 years prior. Bollocks. I went back to work that afternoon, I just wanted to crack on as normal. There was nothing to be done there and then, and this approach became the way I handled most bits of news like this moving forward. Focus on what you can control, not what you can’t.

Sarcoma is a rare form of cancer, mine specifically was a high-grade, radiation-induced soft tissue sarcoma. I was referred to The London Sarcoma Service at UCH. After meeting the oncologist days before Christmas 2017, his plan was for me to have 6 cycles of chemotherapy starting in the new year, followed by a surgical procedure to remove any remaining tumour cells and to take a margin of healthy tissue from around the area for safety. His outlook was positive. The chemotherapy would be brutal but all being well, after a few months of getting through it, a good response, and an operation, I could then get my life back on track. That was all I wanted, to get back to normality as soon as I could. We decided as a family to try and put it to the back of our minds over Christmas and then tackle it head on together, in the new year.

I (like many people, I presume) had no idea about what goes into getting some chemotherapy injected into you. There is a whole period of ‘work up’ where you need to get checked out to make sure you can handle the type of chemotherapy that you are going to be given without damaging your body. For me, that meant liver and kidney function tests, a heart echocardiogram, sperm storage, and having a PICC line put into my arm. A PICC line is a long, thin tube that's inserted through a vein in your arm and passed through to the larger veins near your heart. This allows fast access for medication and prevents you having to be jabbed with needles regularly. So by early January I was all set, plumbed in and good to get on with it.

The chemo was brutal, I would go up to the Macmillan Cancer Centre at UCH in London and have the infusion over three days staying in nearby hospital accommodation before being sent home for two and a half weeks and then repeating the process. At one appointment my oncologist did say that they were giving me a ‘serious bucket’ of chemotherapy each time I visited, and in truth I really felt it. After 3 days in London I would get home and it was like the life had been sucked out of me completely, I was bed-bound for a minimum of 48 hours usually and didn’t want to speak or do anything. Following the initial 48 hours, I would bounce back pretty well day by day just to a good level where all my blood counts had recovered before I was then due back in for another cycle. Between cycles I managed to stay reasonably fit and healthy, and continued to work from home which kept me busy and I am very grateful that I was able to. My friends were great and would come out and visit me when they could and my family were always by my side throughout.

Weekly trips to University College Hospital in London became routine in order to have regular blood tests and have my PICC line re-dressed. I responded extremely well to the chemotherapy in terms of it fighting off the cancer - each scan showed both a reduction in both the size and activity of the sarcoma cells. I couldn’t have asked for a better response. In fact, it got to the stage where after the 5th cycle I was told that I had had a 'complete response’, there was no sign of any cells any more and the decision was made that it would be of no benefit for me to have the 6th and final cycle. I was so relieved, with the symptoms that I was experiencing, and won’t bore you with, I wasn’t sure that I was going to be able to manage a 6th cycle in truth.

On to the first surgery then, and discussions in the lead up to the surgery were pretty traumatic. Initially I thought that it would be conducted endoscopically (via a long, thin camera through the nose) as had been done with my biopsy a few months prior. However, the specialist sarcoma surgeon advised that a more aggressive approach would be appropriate for this type of high grade radiation-induced sarcoma. That involved ‘open’ surgery where I was told there would be incisions on my face and the procedure would therefore carry more risk and scarring. I distinctly remember one appointment where we were initially discussing how he would approach the surgery and he said ‘I am going to make a cut here’ with his finger on my left temple ‘up around the top of the head behind the hairline and down here, peel down the forehead and access the nose this way’ running his finger across, up over the top of my head and down to the opposite temple. I was mortified, and couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Experiences like that stick with you. After a few more appointments, some 3D modelling of my head, and more scans the decision was made by the surgical team to cut into and down the left side of my nose instead (a lateral rhinotomy), remove some tissue, some bone and replace that with some titanium plates. I was still really anxious about this open approach and the facial scarring, but they knew that and did an amazing job. It was going to be a 5 hour operation with a couple of days as an inpatient on the hospital ward to be expected. I went in for surgery at UCH in May 2018, had the operation which went really well, and was discharged the following day.

Following this I was fully on the road to recovery and was ‘cancer free’. I returned to work the following month in June 2018 with my scar on show and quite a bit less hair on my head, but I was so glad to be back to a bit of normality. The commute to London took a bit of getting used to again, but being back at work was massive for me because I loved it. I had some amazing times in the rest of 2018 and into 2019 including moving into a rented flat in London for a year before then buying my own flat outside of London towards the end of 2019. I got back into regular training at the gym, tried all sorts of exercise classes, and competed with work colleagues in the process (thanks Kate). I got into the best physical condition of my life. I had the opportunity to go to California several times with work too. I really made the most of these trips. Together with colleagues (who in reality are my good friends) I went skydiving, go-karting, wine tasting, for nights in San Francisco, group dinners, road trips to Yosemite National Park, and my personal favourite - a tour of the Netflix HQ after a few edibles from the local marijuana dispensary. I also must mention the legendary road trip to Las Vegas via Death Valley over one weekend in my rental convertible red Mustang. 1,100 miles in 48 hours, a stay in Caesar’s Palace and we were back in the office on Monday morning despite all the doubters. I was also lucky enough to travel with friends to Sri Lanka, Holland, Sweden and Austria. Hopefully some of these pictures below convey just how much I did in the year following my surgery. I really bounced back and went for it.

Then unfortunately a couple of weeks after moving into my new flat I had just bought in September 2019, I got two letters through the post from the NHS, one was from the surgical team which was slightly odd. I had not long had a surveillance scan so I was obviously very anxious that they had something to say about that. Turns out my suspicions were correct. I remember that appointment so vividly down to what I was wearing that day. I was sat there with my Mum and there was a doctor covering for my usual oncologist, The first thing she said was ‘have you not heard the news?’. Then she proceeded to tell me that a recurrence had shown up on my latest scan in a similar area to before but slightly higher up near my basal skull (bone at the back of the nose and base of the brain). Initially we were told by the same surgical team that did my operation back in May 2018 that I was going to be referred to a neurosurgeon who specialises in endoscopic surgery to have a conversation about resecting the tumour through the nose with his speciality being in dealing with its proximity to the brain. Before that however, it was suggested that I have some more chemotherapy in an attempt the shrink the tumour before further surgery, similarly to how I was treated before, but with one drug this time. I did have two cycles of chemotherapy but it had little effect and the decision was made to progress with surgery in December 2019. Just before I started that chemotherapy it was the Rugby World Cup final in Tokyo. I knew the start date for my chemotherapy was days afterwards, and so as soon as England beat the All Blacks in the semi-final, I booked tickets for the final and managed to find some questionable flights to fly to Japan with my Dad. Even though England lost, I am so glad we went. We landed back in London the day before my treatment started.

Now it was time to meet with the neurosurgeon at Queen Square hospital - the National hospital for Neurosurgery and Neurology. I went in feeling positive about endoscopic surgery being advanced and minimally invasive however I was in for another shock. The surgeon explained to me that he believed we had one go at getting this operation right and that his approach would be the ‘gold standard’ in trying to achieve the best possible outcome as I ‘have a lot of life left to live'. That approach involved an Alice band shaped cut across the top of my head and a removal of a piece of my skull in order to access the area (a craniotomy) and then remove the tumour and the cribriform plate. Google it if you are feeling brave. He explained the seriousness of the operation, the fact that it would last approximately 8 hours and that there was a 1-2% chance of me having a stroke and dying in theatre. I left feeling mortified. The ‘work up’ in preparation for such a large operation was very daunting. More tests, being told I would wake up in intensive care with a need for one-to-one monitoring for several hours, the possible risks and the list of worries seemed endless. Signing the consent form was a weird experience. I was hopeful that I would be suitably drugged up to not know too much about what was going on. I can’t imagine how my parents and sister dealt with it for all those hours. They were all nearby throughout, at least I could just wake up when it was done. The surgical team who did my first operation the previous year worked together with the neurosurgery team in a joint operation. That is pretty rare, they didn't have to do that, and I will be forever grateful to them for coming together for me and giving it their best.

I mentioned earlier that I had my left eye removed when I was a baby in order to save my life from retinoblastoma. I have worn a prosthetic eye for my whole life and have made every attempt for it to look as ‘normal’ as possible so that no one - not even my closest friends - would need to know that I had one or why I had one. I presume most have had their suspicions that something was slightly ‘off’ at some point, but overall I have kept this to myself my whole life as I never wanted it to define me. The reason I mention this is because one of the risks with this operation was that the skin in the corner of my left eye socket would break down and not heal due to the previous surgery and radiotherapy I had. This was extremely worrying for me, the concept that I would no longer be able to wear my prosthetic eye, something that had only recently started to be comfortable and confident with into my twenties was terrifying.

I was so self-conscious about my artificial left eye growing up. I have thought about it every single day. ‘What were people thinking about how I looked?’ was at the forefront of my mind all the time when speaking to people. It was one of those things that actually was subtle enough that I have often thought it almost would have been better if I had something more obvious on show, that way people may be less curious and inquisitive about it. It felt as though the overall subtlety of it made a few ignorant people feel as though they could pass comment, and certain things will stick with me forever that people have said. For example starting secondary school was torturous for the first few months. I would beg my parents not to take me to school. I have never liked having my picture taken throughout my whole life. I remember overhearing a group that I had met at freshers’ week talking about my ‘weird eyes’ before a night out, they were too drunk to know that I had heard every word. I made sure they knew the next morning to complement their hangovers. Or there was another time going for drinks after work and I overheard someone say that they felt awkward talking to me because they weren’t sure where to look. Each of these experiences would knock my confidence back, but I would build it back up each time eventually. We went to great lengths to get the best prosthetic made in order to achieve the most realistic look possible. For most of my childhood I would get eyes made annually through the NHS. These did the job, but were made using wax moulds and sent off to a factory somewhere to be painted to match a photograph of my good eye so there was room to improve. We went to places in London and to Germany before my parents found a place in Los Angeles that hand made and painted artificial eyes over a couple of days and the results were amazing. I first got the opportunity to go there and get one made when I was 14, and it gave me so much more confidence having an eye that so closely matched my good eye. You can see how pleased I am in the picture below. A lady named Beverley made my eyes for me ever since. Beverley if you are reading this, thank you so much.

All of this made the concept of no longer being able to have an artificial eye particularly terrifying for me. I wrote to the surgeons asking them to do their utmost to help ensure I could continue to wear my prosthetic, and I know they did. I had the operation and it went well, I was under general anaesthetic for 8 hours and woke up with a bit of a sore head on a ward for stroke and brain injury patients. The experience on the ward was pretty awful. I had a drain in the back of my head that got in the way when I tried to sleep, and there were a lot of patients there in pain or struggling which was not nice to see. For days I had to be assisted to walk to the bathroom and was regularly asked where I was, what the date was and if I could wiggle my toes. I understand the reasons why, but it all felt too much and that I just shouldn’t have been there (no one should have to be there but you know what I mean). One evening a patient opposite me got himself up to go to the bathroom, collapsed and went into cardiac arrest. Staff on the ward tried to resuscitate him for about 45 minutes before they pronounced him dead. That was brutal. I was expected to be on the ward for up to 2 weeks but I broke out of there after 7 days luckily. Back home for Christmas.

Then came a few more complications just to see out 2019, I was violently sick on Boxing Day evening and went to the local A&E where it turns out I had contracted norovirus. I was sent back up to Queen Square hospital as a precaution and they kept me there on fluids for a few days. Following this, I checked the area on my left eye and it was not healing, in fact there was a small black hole there which was pretty disconcerting. My GP had a look and suggested that we go up to UCH as the tissue was dying in that area. So back up to London we went and it turns out I had an infection called pseudomonas. The area needed to be cleaned out and re-constructed so I wasn't left with a hole in the corner of my eye. This meant more surgery. So to see in 2020 I had another operation for some reconstruction. This time they would remove the titanium plates from my nose (as pseudomonas clings to metal), flush the area and cover the hole with a paramedian forehead flap - google it if you are feeling brave. This meant another incision, this time right down the centre of my forehead in order to get some skin with a blood supply channelled down to cover the hole. Again, google it if you are feeling brave. Another operation that lasted a few hours and I woke up in intensive care with a pump attached to me for the pain relief. Safe to say it got well used for a few days in hospital before I managed to get home for a bit of recovery. Unfortunately I have not been able to wear my prosthetic eye since that initial operation at Queen Square. I doubt I ever will be able to wear one again, but for now that is not my main concern.

After a period of recovery and healing from the surgery, the decision was made for me to have some more radiotherapy. In the words of the oncologist specialising in radiotherapy ‘there is more chance of it coming back if you have no radiotherapy than if you have more radiotherapy’. Time for some radiotherapy then. The global pandemic had just kicked off, and now it was time for six weeks of radiotherapy to kick off for me. Six weeks of travelling into London every weekday to lay on a bench with my face clamped to it in a plastic mould to keep it still for about 30 minutes. At least there was next to no traffic going to London - always find the positive. Radiotherapy is pretty nasty, it makes you pretty tired and burns your skin, but I got through it and was relieved when it was over. Time to go home, recover, bake a lot, try and stay fit on my bike and await future scans to see if this had all done the desired job.

From April, like everyone else, I was locked down and working from home. Taking part in lockdown quizzes (always off camera), lots of calls and playing way too much Call of Duty Warzone each evening. Then in July I started to get headaches which got progressively worse each day, especially in the evenings. It got to the stage where no medication would touch it and the pain was probably an 8 or pushing a 9 out of 10. As a result we thought it best that I be taken up to UCH to get checked out. I was admitted as an inpatient, had a set of scans and awaited the results. My oncologist came in looking pretty disheartened. My parents were with me when he delivered the news that the sarcoma had returned aggressively in the same area. Not only that but it had now also spread to my lower spine and at the back of my head on the lining of my brain. This was the biggest blow to date because the news came with the fact that it had spread, but also that my options in terms of treatment had now almost run out - my diagnosis was now terminal. I don’t really know how I handled it at the time, it is all a bit of a blur. Receiving that news at any age is horrific but at aged 26 it feels particularly cruel.

As you can imagine this led to a lot of heartfelt conversations between me and my parents, almost as if we felt as though there were things we had to tell each other while we had the chance to still be together in that hospital room. We didn’t know how much time I had left. Luckily for me, my oncologist had not totally given up on me just yet. He mentioned a treatment developed by a colleague of his which was a combination of two chemotherapy drugs that had shown some success in other sarcoma patients with advanced disease. The Professor who developed the treatment came in and saw me and my parents to explain it and her hopes for me. Both doctors were keen to manage any expectations, advising that they were not at all hopeful that this was going to work, and also said that they would completely understand if I did not want to go ahead with the treatment either, as I had already been through enough. I then asked the question I didn’t really want an answer to; ‘if I decided not to go ahead with the treatment how long will I live for?’ The response was ‘hard to say, could be weeks, could be months’. Bollocks. I decided to go ahead, I had to give it a go and I am glad I did because it has given me way more time than initially thought I would have. I am still here writing this in December 2021 a year and a half later. The regime for this chemotherapy was one cycle every three weeks. One cycle was split into two parts ‘day one’ of the three week period would be an IV infusion of one drug, I would then have a week off and return for another IV infusion of both drugs on ‘day eight’, then I would get two weeks off before repeating this for the next cycle. I managed twelve cycles of this, which is a lot. This treatment saw me from diagnosis in July 2020 through to May 2021 when I then needed to take a break. I was reaching the limit that a person can safely have before starting to damage certain organs. Not only this, it was seriously wiping me out after each infusion, and I was struggling both physically and mentally with the side-effects. The decision was made to have a break from treatment after discussing it with my family and my oncologist. The oncologist said that I had already exceeded all of their expectations in terms of my response to the treatment and how I had handled it.

Despite struggling periodically with the treatment, I had some great times at the end of 2020 and well into 2021. Particularly considering what had been going on in my life, and the fact that the global pandemic continued to be an ever present thorn in everyone’s side over the winter. I was advised to just go and do as many things that I enjoyed as possible as time was now precious. We managed to get away within the UK on small trips to Dorset, Brecon, and Lancashire when allowed. I trained regularly over FaceTime with an exercise physiologist specialising in training for chemotherapy patients called Tom, who despite having still never met in person, has become a real friend. My sister and I went and climbed Snowdon, I hiked up Pen-y-Fan with my Mum and went and flew in a Spitfire with my Dad. I took up and became a bit obsessed with golf thanks to encouragement from my mate Dan, and managed to re-light a passion for it amongst my two uncles which has been great fun. It is important to remember that throughout all the shit, me and my family have tried to make the most of our time and where possible live to the maximum each day. I am not looking back now writing this thinking that I should have done more.

August 2021 - time for another hospital admission following another extremely painful headache. Initially this was to the local A&E before being taken up to UCH again and being admitted. More scans showed that the tumour in my nose was active again and that it had now shown up in my left sinus area as well, after a rest period of no chemotherapy. Discussions with my oncologist were more optimistic than this exact time the previous year. He had ideas about a few other chemotherapy drugs to try so that was the new plan, start a new drug and see how that goes. I tried the new drug and whilst it did prove to slow things down, it was not having the desired effect. This exact process repeated few weeks later, another hospital admission and scans with the subsequent decision to switch to a new drug which took me to October 2021. Time for another hospital admission for a suspected infection, the swelling on my left cheek was getting quite large and it was suggested that I have a course of IV antibiotics over two weeks in order to bring the swelling down. These antibiotics had no effect on the swelling whilst I was admitted in hospital and scans showed that it was due to the sinus tumour growth, not from infection. I asked the sarcoma surgeon to come and see me. He did and said he would speak to a colleague of his to see if there was something he could do to help with the inflammation from a surgical perspective. An ENT surgeon came and saw me and the decision was made for me to have a de-bulking procedure which lasted a couple of hours and relieved pressure in my cheek. Unfortunately the benefits didn’t last too long and the inflammation has since returned and I now look like a squirrel storing his nuts in one side of its mouth. Rather than being inflammation from the surgery, scans showed that the tumour had returned rapidly and filled the area in my left cheek. Bollocks.

Since then I have been admitted again at the start of November for you guessed it, a suspected infection. Actually the admission turned out to be timely because I started to experience severe pain whilst in hospital. My regular pain medication was not touching it, and I was having to ask for top up pain relief that would be injected into my stomach to deliver relief as quickly as possible. Even with this I could not get on top of it, as the nursing staff were often so busy that they couldn’t get to me quickly enough to administer the injections I needed. The decision was made to put me on to a syringe driver - a device that is permanently connected to me via a canular in order to constantly drip feed pain relief medication into my system. I managed to break out of hospital after a few days and have since been in contact with my local palliative care team who are helping me to manage my pain medication locally rather than having to communicate with the team in London all the time and avoid going up there.

The team at Thames Hospice are amazing, and I cannot believe the job they do funded purely on donations. Despite this, being so involved with a hospice at my age feels so wrong, but I recognise just how important they are for me and my family and I am not sure what we would do without them now. Whilst I was on a syringe driver at home they would come out every day to change it and give me my dose of pain relief for the next 24 hours. They are always at the end of the phone 24/7 and I can’t speak highly enough of them. I now use their counselling service regularly which is proving to be a great help for me too. The same goes for the team of District Nurses that will come out and check on me after a quick phone call, they are truly amazing. Also, I still managed to play 9 holes of golf with my Uncles the day after getting home (and unsurprisingly I lost).

Most recently I have had another scan to see how my latest chemotherapy is working, and this time it has shown a ‘mixed response’. The area of tumour at the basal skull has responded, whilst the tumour in my cheek unfortunately still continues to grow. At least it is that way around. So the decision has been made to try another cycle of the current chemotherapy drug and then re-scan. My oncologist told me the other day that I will have reached a fifth-line of chemotherapy. Most people don’t make it beyond two. I am not sharing that because I think it is a personal achievement, but it is worth mentioning as it makes me feel just a little bit lucky in a situation that overall could not be more unlucky. He also has still has not given up on me just yet. We talk about his ideas and thoughts on other drugs that might be suitable for me to try, and I have also been referred for a couple of clinical trials which would be amazing to get the opportunity to be a part of if I meet the criteria. Onwards and upwards, one day at a time. I’ll post any future updates here.

Michael x

A few final thoughts…

I have been thinking recently about when people talk about cancer patients ‘fighting’ or ‘losing their battle’ with cancer. What a load of bullshit that is. Please don’t ever say or let anyone else say “Michael lost his battle with cancer”. This came from a quote that I read from a comedian named Norm Macdonald who sadly passed away from cancer in September this year. He said this after experiencing his Uncle being treated for cancer…

“When I hear a guy lost a battle to cancer, that really did bother me, that that’s a term. It implies that he failed and that somebody else that defeated cancer is heroic and courageous.”

Norm Macdonald also said this which I love…

“I’m pretty sure, I’m not a doctor, but I’m pretty sure if you die, the cancer dies at the same time. That’s not a loss. That’s a draw.”